This week, Christine and I were lucky enough to shadow Dr. Huang, a cardiologist, as he was performing a couple cardiac catheterization procedures. Because there hasn’t been too much learning in terms of percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) during my first year of medical school, I think that it’s appropriate to dedicate an entire post about the fascinating world of coronary artery disease (CAD) management based on my experiences in Cath Lab. Due to recent advances in medical care, CAD is almost always due to atheromatous narrowing and subsequent occlusion of the vessel. This occlusion (usually in the form of a plaque), when it produces >50% diameter stenosis or >75% reduction in cross-sectional area, there will be reduced blood flow through the coronary arteries perfusing the heart. This will manifest as angina, silent ischemia, myocardial infarction, arrhythmias, heart failure, and in severe cases, sudden death. Although there are many non-invasive investigations that can be used, the current gold standard study for CAD is PCI. As the name states, it is an invasive procedure that includes ventricular angiography and haemodynamic measurements. Although anesthetics are used, arterial access (by either femoral or radial) is still uncomfortable. Insertion of an arterial sheath with a homeostatic valve helps to minimize blood loss and catheter exchange. Many types of catheter can be used and are due to the variety, individualization can be achieved. Contrast medium (fluoroscopy) is injected through the catheter lumen and moving x-ray images are obtained and recorded. Other catheters can be used for graft angiography. Shown below is a typical cardiac angiography procedure (courtesy of https://www.uthsc.edu/cardiology/articles/abc%20of%20CAD%20cath%20BMJ03.pdf):

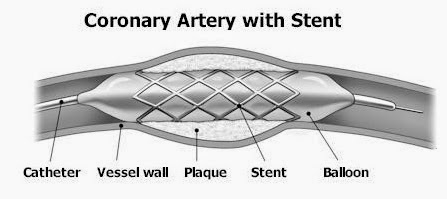

If there is significant stenosis or occlusion, PCI is indicated. While it is still invasive, it is a non-surgical procedure that hopefully unblocks narrowed coronary arteries. Although there are many different PCI procedures, the two most common are balloon catheter angioplasty and stent deployment. In balloon catheter angioplasty, a special type of cardiac catheter is directed with a small balloon around it into the narrowed area. The balloon is then expanded, which pushes the plaque to the sides of the artery where it remains with an end effect of normalizing the artery size. What usually follows is stent placement, which is a small and hollow metal mesh tube that keeps the artery open (photo courtesy of: http://www.cpmc.org/learning/documents/cardiaccath-ws.html). After the procedure, tissue will begin to form over it and eventually, the stent will be completely covered. Anti-platelet drugs are used to prevent blood clots from forming inside the stent (a common complication). Sometimes, even with this intervention, stenosis can reoccur either upstream or downstream from the treated area. In the cases that we saw, many patients had re-stenosis after a year, so a new stent had to be deployed. Drug-eluting stents helps to mitigate this issue, as the stent is coated with an anti-proliferative drug (like Paclitaxel) to prevent overgrowth of scar tissue.

Personal Note: There is a lot of PCI cases in this department. Dr. Huang says it is usually due to the refusal of the patient and his/her family in doing a coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery. There have been numerous studies done of the effectiveness of CABG versus PCI in CAD management. He suspects that it is due to their culture and prior experiences that deter them from a more invasive and surgical procedure. In addition, drug eluting stents are not covered by NHI, meaning that even if it’s more effective the sheer cost of the stent (~$2.5k USD) will deter many patients from choosing it. This is the primary reason why many patients come back since their initial stent deployment is now ineffective and the coronary artery has re-narrowed. Dr. Huang routinely does PCI via radial artery insertion. In the United States, it is more common to use the femoral artery route. This is mainly due to the fact that the femoral artery is a more direct approach and the radial artery is more difficult to insert a catheter. However, it seems that we are starting to perform the radial artery approach due to two reasons: risk reduction of major bleeding and vascular complications (although this does not yield a reduction of major adverse cardiovascular events) and faster patient turnaround time. A venography (similar to angiography, but for veins) was performed on Tuesday using the femoral approach. The patient had to be fully sedated and the majority of the procedure was spent minimizing complications and waiting for the patient to wake up. With a radial approach, the patient came out of the procedure in under 5 minutes and fully awake to be wheeled next to Dr. Huang to discuss the procedure outcome.

No comments:

Post a Comment